Welcome to The Backboard, the new home for some of my tennis thoughts and musings. This column will appear every Tuesday here at The Changeover. You can find past editions of The Backboard here.

The Walking Wounded Part 2: Too Much Money on the Table

A little over a month ago, I wrote in this space about what would motivate pros like Janko Tipsarevic and Juan Mónaco to keep showing up at tournaments when they were struggling with injuries and losing in the first round of said events. At that point, Tipsarevic had lost four straight first round matches and hadn’t won a set of tennis since the Australian Open.

For the purposes of this column, we’ll stick with Janko Tipsarevic, since Mónaco has won six of his past nine matches and has started to look more and more like the player he was for most of 2012.

Just before I wrote the column referenced above, Tipsarevic had lost 2-6, 0-6 to Ernests Gulbis. However, the Serb would “rebound” in Miami, beating Dudi Sela (ranked #127) and Kevin Anderson before bowing out to Gilles Simon. Tipsarevic then played in Monte-Carlo, adding another first round loss to his 2013 resumé (to Grigor Dimitrov) and then lost in the quarterfinals in Bucharest the following week (to García López). It’s important to note that given Tipsarevic’s ranking, he only had to win one match to reach the quarters at that small ATP 250 event.

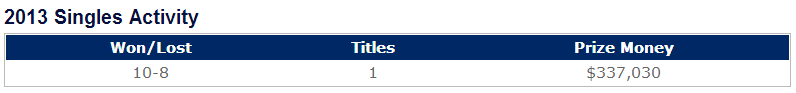

Overall, Janko Tipsarevic has won 10 matches in 2013, and lost eight. He’s barely over .500, but he’s still in the top 10. More importantly … Tipsarevic has made $337,030, according to the ATP website:

Now, this is not meant to trash Janko Tipsarevic for having such a mediocre year. The point I want to make is one that I regrettably didn’t make a month ago: look at the amount of money Tipsarevic has earned in 2013. It’s a nice amount, no?

Here’s what I wanted to see: just how much money is out there for showing up and losing in the first round? Note that this is just prize money: I have no idea if Tipsarevic’s endorsement deals give him any incentive to show up at events, or if those events, particularly the small ones, give him any appearance fees (Tipsarevic was the top seed in Bucharest and currently is the top seed in Munich).

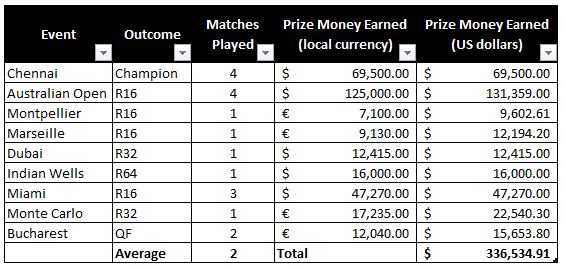

I logged all of Tipsarevic’s tournaments as well as how well he did there and how much money he made. Heck, I even used oanda.com to figure out what the exchange rate was at the time (Tipsarevic earned prize money in US dollars, Australian Dollars, and of course, Euros). Here is what I came up with:

As you can see, my estimate is quite close to what the ATP credits Tipsarevic with – the discrepancy is just under $500. Who knows what rate he used to exchange his money, and when he did it – I merely used the exchange rate of the approximate day on which he would have received his check.

You’ll immediately notice two things: a large chunk of his money comes from his title run in Chennai and from the four matches he played at the Australian Open. You’ll also notice that Tipsarevic is averaging a measly two matches per tournament. Not exactly top 10-esque, right?

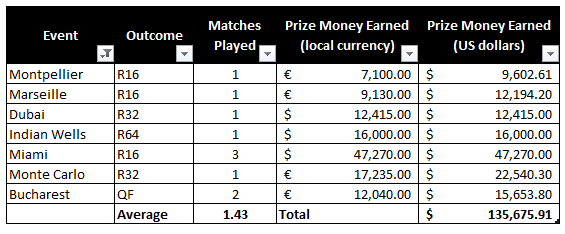

Anyway, let’s take out those high-grossing tournaments (which also account for 44% of Tisparevic’s matches in 2013). Here is what we get:

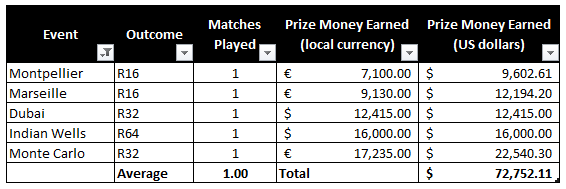

That’s still a pretty nice sum, right? Six figures for just 10 matches – seven of which Tipsarevic lost – is nothing to sneeze at. Lastly, let’s look at the table with the tournaments where Tipsarevic didn’t even win a round:

That’s still a super nice number, right? Seventy-two thousand dollars for losing five matches? That’s awesome! That’s an average of $14,550.42 per match. And here is the key that makes that number significantly nicer than it would be if Tipsarevic were merely a journeyman: being ranked high enough to be seeded at events. Why? Because that means (outside of the Slams) Tipsarevic gets a bye into the second round.

And that means a significant bump in earnings.

That’s the case in Monte Carlo, where Tipsarevic got Round of 32 money even though he only played one match. Daniel Gimeno-Traver, on the other hand, did play in the first round (Round of 64 – lost to Youzhny), and only got 9,305 Euros for his troubles, which is 46% less than what Tipsarevic got purely due to his higher ranking. Both men played a single match at the Principality, and both lost.

The same phenomenon applies to Marseille: Tipsarevic got a first round bye, lost in the second round, and pocketed 9,130 Euros for it. Jarkko Nieminen did play in the first round and lost. His paycheck? 5,410 Euros. Which is 40% less than what Tipsarevic got for playing the exact same number of matches.

Again, the larger point is not to trash Tipsarevic, or to denounce the fairness of first round byes: what I want to illustrate is why it’s perfectly understandable that guys with a high ranking show up at tournaments even though they’re struggling with niggling injuries. There’s a lot of money to be made, no matter the size of the tournament (though if you’re getting a first round bye at a Masters 1000 event, it’s an even sweeter – and mandatory for top players – payday).

And the best part is that you don’t even need to win in order to cash in. Which helps when you’re dealing with injuries.

Add to the fact that Janko Tipsarevic is 28 years old, and that tennis doesn’t offer guaranteed income (like NBA players, for example), and the decision is much easier to understand. Would you leave that much money on the table? I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t.

Also, you can argue that Tipsarevic has earned the right to do what he’s done in the early part of 2013: his ranking is made up of real points earned at big tournaments (two Masters 1000 semis, US Open quarterfinals), plus titles in Chennai and Stuttgart. Why shouldn’t he cash in on his top 10 performance in 2012?

*****

Janko, who is still ranked No. 10 in the world, is slated to play this week in Munich, Germany, where he’s the top seed. But his real challenge will be the following week, when he’ll attempt to defend 360 semifinalist points at the Madrid Masters 1000. A good showing in that specific Masters 1000 event is key: an early loss coupled with good results from the players behind him in the rankings put him at risk of not getting those first round byes at Masters events.

For example, Rome only awards first round byes to the top eight seeds. Tipsarevic earned that privilege last year, but is unlikely to do it this year. In terms of the smaller events, Tipsarevic would face more competition to be the top seed at 250s, since more guys would be ranked ahead of him. Not only that, but losing his top 10 status would make him less appealing for the tournament directors of those events.

Which makes me wonder if guys should probably think more long-term whenever they’re injured, since a bad run of results would hurt their rankings anyway. Surely their bodies would appreciate not having to travel every week. Yet I can totally understand going for that safe paycheck if they know their injury isn’t that serious.

Like Lindsay told me when we were discussing this, that paycheck is the closest thing a tennis player has to a regular salary.

Things I’ve Read Recently That Made Me Think

The Unlikeliness of Inducing Double Faults – by Jeff Sackman (Heavy Topspin)

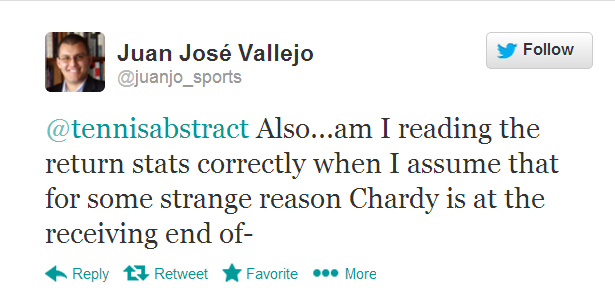

True story: a little over a week ago, I was looking at the wonderful tennisabstract.com data. After clicking around and oohing and aahing, I found myself puzzled at something: Jeremy Chardy had the highest “Double Fault against” rating of any tennis player for the entire 2012 season. Did that mean that nobody in the ATP World Tour “induces” more double-faults than … Jeremy Chardy? How does that make any sense? Just to be sure, I tweeted Jeff asking for clarification:

You can see Jeff’s response under my last tweet. My mind was blown: the numbers go against everything we’ve been hearing for years, about how double faults are somehow provoked by great returns/returners. I’m sure all of you can remember a broadcast when somebody made that point. Heck, I might’ve made that same erroneous point somewhere on this site.

Well, Jeff wrote the above piece on why that’s just not true. Great returners don’t induce a greater number of double faults from their opponents than mediocre returners. And there’s no point trying to figure out why Jeremy Chardy topped the list on this specific stat – sometimes Lady Fortune works in mysterious ways.

If anything, the fact that Jeremy Chardy tops that list should indicate to us that conventional wisdom might be trying to sell us hokum. And thankfully, there are people like Jeff who take time to debunk said hokum quite thoroughly.

Al Jazeera eyeballing Tennis Channel – by Claire Atkinson (New York Post)

This story, from April 18, made me happy. Al Jazeera, with its strong financial muscle and international worldview, would be a perfect new owner for the Tennis Channel (to clarify, the Tennis Channel is not for sale – as far as we know). U.S readers who have experienced the channel would acknowledge that while it’s fantastic to have a TV outlet that’s purely devoted to tennis, the channel could use a myriad of improvements. To put it simply: the Tennis Channel could be so. much. better. After all, they’re the network that gave Murphy Jensen a travel show (click at your own peril).

However, this report came from the New York Post, so I shouldn’t have gotten too excited. Why? Well, look at the piece below:

Al Jazeera not interested in playing ball with Tennis Channel – by Joe Flint (Los Angeles Times)

It’s from April 25, and it shot my enthusiasm down. Except … this might not be the end of the story. For one, I’m sure any prospective buyer would like to see how the legal battle between the Tennis Channel and Comcast shakes out. It wouldn’t make sense to invest in a TV channel that might be on the losing end of a dispute that would deny it access to millions of homes.

Network purchases are messy affairs that never get done quickly, so I’m sure this won’t be the last time we hear about this. And again, much depends on which way the court case goes.

Still, hope never dies.

Marc López: “No creo que los Bryan sean los mejores de la historia” – by Rafael Plaza (Punto de Break)

Translation: “I don’t think the Bryans are the best in history.”

Here’s the full quote, which I think is very interesting (and makes a valid point):

“No lo creo. De lo que yo he vivido sí, pero antes los dobles estaban más disputados y había más parejas sólidas. Esto tendríamos que hablarlo con Nestor, con Zimonjic… con estos jugadores que han vivido varias épocas porque ya tienen casi 40 años. De los que yo he visto, sí. Los hermanos Bryan son la pareja más difícil contra la que he jugado, pero no creo que sean los mejores de la historia.”

Translation: “I don’t think so (about the Bryans being the GOATs). Of what I’ve lived through, yes, but doubles used to be more competitive in other years, and you had more great teams. We would have to discuss this with [Daniel] Nestor, with [Nenad] Zimonjic… with those players who’ve lived through many eras because they’re close to being 40 years old. Of those [teams] that I’ve seen, yes. The Bryans are the toughest team that I’ve played against, but I don’t think they’re the best in history.”

I think it’s perfectly valid to differentiate the “best of this era” versus “best ever” conversations. Particularly in tennis, since the sport has changed so dramatically from decade to decade. Doubles, as we know, has seen it’s fair share of changes: ATP doubles events have their own scoring system (no Ad and no third set in favor of a super-tiebreaker). But the other development of the past 20 years is that elite singles players don’t play doubles regularly anymore. As the singles game has become more physical, the elite has prioritized the more lucrative path and kept doubles as something they do to get acquainted with a new surface, a way to practice specific elements of their singles game, or as a way to get match fit after a long layover.

The Bryans are the most accomplished duo in doubles history. That much has been made clear recently. But I do think it’s more productive (and interesting) to talk about the context surrounding specific eras and teams than to just hand over GOAT status. Also, it would be more interesting if we discussed these things in terms of a Mount Rushmore and not a solitary GOAT. That would allow the past greats to be fully appreciated for their achievements.

At any rate, the interview above is quite fascinating. Marc López is very open about what he thinks of his current ranking (“circumstantial” – he says he’s a No. 3-ranked player who doesn’t see the No. 1 ranking as a possibility), what makes his partnership with Marcel Granollers great, and many, many other things. Highly recommended for Spanish speakers and those adventurous enough to use Google Translate.

Tweet That Got Favorited For Very Obvious Reasons

Translation: “Player or Line Judge???”

Translation of Safina’s comment: “Hahahahaha that’s a good one!!!

This is just a fantastic use of social media by a pro athlete to make a nerdy tennis point at the same time he’s giving his friend a hard time about said tennis point. As we know, Rafael Nadal and Juan Mónaco are great friends, and the intent here is pretty obvious: to bust Nadal’s chops about his return position, which is closer to the back fence than to the baseline. This is good natured fun with the added bonus of a great photo.

Much has been discussed and tweeted about Nadal’s tendency to stand way back to return first and second serves. Only in the final matches at Indian Wells did we see Nadal start to step in closer to the baseline for second serves, but now that he’s back on the clay, Nadal has gone back to this extreme return position. I remarked last week about how this return philosophy might be working really well against most people (after all, Nadal has only lost two matches since his comeback – none of them before a final), but not against his main rival these days, World No. 1 Novak Djokovic.

Let’s be clear, though: Nadal’s return stance is not a terrible idea. By standing that far back, Nadal gives himself a higher chance of getting returns back (since his quickness gives him a little extra time to get to serves), but most importantly, it affords him the opportunity to hit forehand returns. Unlike people who stand closer to the baseline and intend to run around their backhands, Nadal doesn’t have to “cheat” beforehand in order to do that – he can simply react to the serve and then proceed to run around his backhand and belt one of his great forehands with loads of spin and pace.

Also, Nadal gives himself a chance to hit full swings on his returns, instead of the abbreviated swings most people use on returns (it may be that he doesn’t feel confident enough to return that way yet). As with everything in life, there are pros and cons to every approach. Andre Agassi was fanatical about standing as close to the baseline as possible for returns, and the price he had to pay was getting aced a lot (his lack of reach didn’t help, either) by people who could hit their spots. Nadal won’t get aced a lot, but if his returns don’t have enough pace and depth, he’ll be giving a lot of real estate to his opponents on that first rally ball. But his problem is that Djokovic has become quite adept at neutralizing the “good” returns Nadal produces with this stance.

It’ll be interesting to see if Nadal alters anything in his return stance in Madrid or Rome, especially if he plays Djokovic again. As he would say, “we gonna see, no?”

Music Used to Write this Column

I’ve had a very long and evolving relationship with Smashing Pumpkins’ magnum opus Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. It’s been kind of like a “When Harry Met Sally” thing. I remember when it came out: I was about to become a teenager. For some reason, I hated “Tonight, Tonight.” I hated the song, and I hated the video for it (years later while in film school I learned that it was a touching tribute to Georges Méliès, one of cinema’s founding fathers). I did love “1979” right from the get-go, though. It remains the most beautiful song about the adolescence I never had – coupled with the iconic music video for it.

Back in the mid-to-late ’90s, music consumption was still centered around buying the CDs and watching the music videos for an album’s singles. Of course, there was radio, too, but in Ecuador that wasn’t much of an option. I didn’t pony up the cash for the double album, so the years went by without us getting any closer. Fortunately during these years of estrangement I did realize that “Tonight, Tonight” is a gorgeous song. I didn’t hate it anymore.

Then, when I was living in Argentina for film school, I finally listened to the whole thing for the first time. I found so many gorgeous songs inside it (“To Forgive,” Cupid De Locke,” “Galapogos,” “Thirty Three,” etc.) but was also annoyed at Billy Corgan’s ill-fated wannabe hard rocker ventures (“Jellybelly,” “Zero,” “Where Boys Fear to Tread,” and others). I remember making a playlist of only the “good” parts of Mellon Collie. It consisted of no more than 10 songs out of the 28 that the double album contains (as a bit of trivia, Corgan wrote all but two of those. I will always find that astounding).

A year or so ago, I decided to give the entire body of Mellon Collie another try. And I surprised myself by noticing how I could now tolerate Corgan’s hard rock excesses. I even liked them. The usual favorites were still the usual favorites, and I found that they are actually enhanced when they pop up amid the chaos.

Mellon Collie is truly a remarkable achievement. It’s the only double album I listen to from beginning to end, and I think I love it a little more every time I embark on that two-hour journey. It came out almost 18 years ago, but I’ve only fallen deeply in love with it within the past year or so. Even though we’ve known each other since it came out. My relationship with it has definitely been a slow-burning affair.

You know, like “When Harry Met Sally.”

Here’s the song that called me back to Mellon Collie this time, the very underrated “In the Arms of Sleep:”

I wonder if Djokovic has the fewest double faults served against him because he’s such a great returner? It sounds counter-intuitive, but it could be that his opponents don’t go for amazing serves against him, rather just to get a decent serve in, since they know that serve is likely to come back. Just speculating…

Juan Jose, what does Marc say here? Google really garbles the translation. Does he say that Rafa sometimes gets him (Marc) in trouble or that Marc sometimes gets Rafa in trouble? 🙂

P. ¿Te reconocen más por la calle desde que eres el número tres del mundo en dobles?

R. Nunca he sido mediático y nunca me han reconocido. Ahora alguien sí que me reconoce o yo veo que me reconocen o les sueno, aunque no me digan nada. Siempre lo he visto cuando voy con Rafa por la calle y es algo que me hace gracia y me da mucha vergüenza. Pero está muy bien que la gente te reconozca o quiera hacerse una foto contigo porque les gusta como juegas a tenis es algo que me agrada. No sé si seguirá así el tema, ojalá sí.

P. Muy divertido el ‘Harlem Shake’ de Montecarlo. Estelar Raonic…

R. Otra cosa a la que Rafa me hizo salir (risas). Somos amigos, pero mete en unos líos… No conocía a Raonic en esa faceta. En el vestuario y en la pista es serio y ahí se volvió loco. Y mira que había perdido en el desempate del tercer set por la mañana… Nos lo pasamos muy bien en la cena y fue algo gracioso.

Totally out unrelated to the column, but… I miss your old icon. Many is a day that I’ve lost focus at work and remembered your icon, with your eyes peering at me and “quietly judging me”. It made me smile and re-focus!