Welcome to The Backboard, the new home for some of my tennis thoughts and musings. This column will appear every Monday here at The Changeover (this week is an exception). You can find past editions of The Backboard here.

Analyzing All the Key Points of the Monte Carlo Final

A few days ago, when I wrote a post about Rafael Nadal’s efficiency and consistency in Monte Carlo, Ang tweeted to me this interesting thought: would it be possible to see what happened during the key points of a match? What happened during all the game points, break points, set points? Did those pivotal instances of a match end in winners or in errors? As we know, not even the great TennisTV stats let you see that sort of thing, and even if we had the official match scorecard, we could only gleam a small percentage of this kind of information (more on scorecards below).

This idea kept going around my head for the rest of the week, and finally, I had a plan. I had already decided to do a LiveAnalysis post of the Monte Carlo final between Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal. In those posts I always include updates after every game, and I usually mention how games end. What if for this specific match I paid a little extra attention and logged some additional details about all the game points, break points, set points, and match points that would take place during the match?

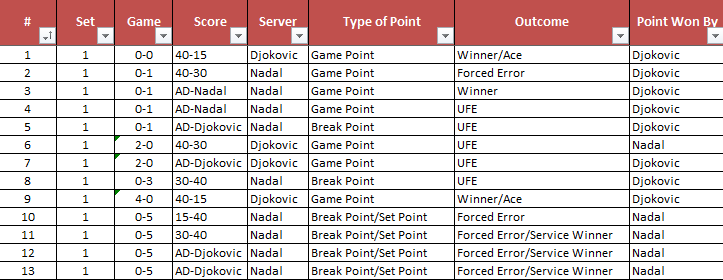

I went ahead and did that. Then yesterday I tried to make sense of the information. With the help of Excel, I created a log of all the key points. Here’s a little snippet of what the log looks like:

As I started building the log, I immediately realized I had to make some important decisions. As in, what kinds of outcomes would I list for points? I came up with these three:

1. Winner/Ace

2. Forced Error/Service Winner

3. Unforced Error/Double-Fault

After I finished the log and I began the process of analyzing the information I had collected, I realized that this was a good opportunity to make a point about a problem I have with the “winner” statistic. As we know, winners are not part of the official set of tennis stats, but all the big events (Masters 1000, the Premier Mandatories and the Slams) assign staff to tally them, along with unforced errors and net points. However, very few events tally forced errors, all of which have the same value on a tennis court as a winner (this has prompted some people to tally some extreme forced errors as winners, which is not an ideal outcome). There are players like Rafael Nadal, who by the nature of their shots (the heavy topspin instead of flatter shots), generate a lot more forced errors than clean winners. At the end of the day, any shot that forces an error indicates aggressive play, and should be counted as such.

Hence, for the analysis below I decided to keep Winners/Aces and Forced Errors/Service Winners separate, but I added them together in a stat called Point-Ending Shot.

For this initial approach to analyzing key points, I didn’t segregate unforced errors as backhand or forehand unforced errors. At this stage, I just wanted to separate all point-ending shots from errors. Maybe this additional variable could be added in the future (which would complicate all my Excel formulas, but that’s a nerdy challenge I’ll always be willing to accept).

Analysis

Now that the stage is set, let’s get down to what I found:

– 36 Key Points were played in the Monte Carlo final. 20 were won by Novak Djokovic and 16 by Rafael Nadal.

– 61% of Key Points were won on Point-Ending Shots.

– Interestingly enough, Nadal won 10 of the 19 Key Points played in the first set. This might seem counter-intuitive given the set score (6-2 in favor of Djokovic), but it makes sense, given that Nadal saved 7 break points that doubled as set points. He ended up double-faulting on that eighth set point, but the way Rafael staved off those set points (which came in two separate games) is what got him going and made the second set a much tighter affair. Djokovic won 11 of the 17 Key Points in that tiebreak set.

– On Key Points played on Nadal’s serve, 67% of them were won on Point-Ending Shots. By comparison, only 53% of Key Points played on Djokovic’s serve were won by Point-Ending Shots, which I find fascinating.

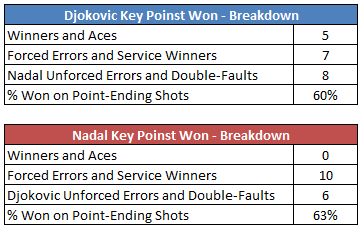

– The 2013 Monte Carlo champion won 60% of his Key Points via Point-Ending Shots. This means that Nadal donated 40% of those points via unforced errors. On the other hand, Nadal won 63% of his Key Points via Point-Ending Shots.

Here’s the detailed breakdown of Djokovic and Nadal’s Key Points won during the entire match:

You’ll notice something interesting right away: Nadal didn’t win a single Key Point via an Ace or a clean winner. Again, this is not a criticism of Nadal, given that he won 10 Key Points via Forced Errors/Service Winners (plus, we’re talking about a match played on clay. And Nadal was credited with 18 winners for the match, just 7 fewer than Djokovic). But this illustrates why the “winner” stat is not the most adequate to measure the aggression of some players.

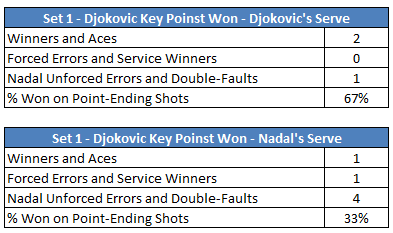

Now, what I wanted to see is how either men fared on Key Points depending on who was serving during said points. Here’s Djokovic’s Set 1 breakdown:

Notice how the percentage of Key Points won on Point-Ending Shots changes dramatically depending on who was serving. I’m guessing Rafael Nadal won’t be too pleased to see that he donated two thirds of Key Points on his own serve via a double-fault.

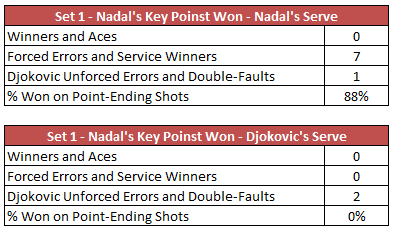

Here’s Nadal’s Set 1 breakdown:

You’ll notice that the pattern we saw in Djokovic’s Set 1 breakdown is even more dramatic here. You can clearly see how hard Nadal had to work for Key Points in the first set of the Monte Carlo final: only one out of eight were given to him via an unforced error. On the other hand, you can see that Nadal was gifted both Key Points on Djokovic’s serve. Remember this scenario (Nadal Key Points won on Djokovic’s serve).

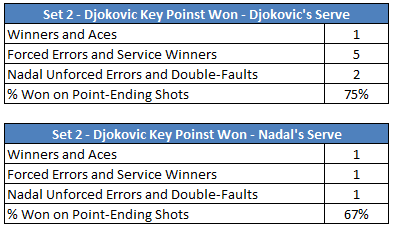

Let’s move on to Set 2. Here’s Djokovic’s breakdown:

Notice how many Key Points Djokovic had to win on his own serve – and how high the percentage of them were won on Point-Ending Shots. Notice, too, how few Key Points he was able to win on Nadal’s serve. Clearly Nadal wasn’t in a giving mood in the second set.

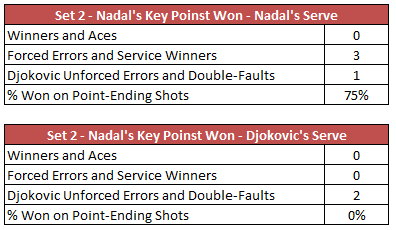

Here’s Nadal’s Set 2 breakdown:

Notice the second box. Isn’t it interesting that for the entire match Nadal wasn’t able to win a single Key Point on Djokovic’s serve via a Point-Ending Shot? All four Key Points he won in this scenario came via Djokovic unforced errors.

Conclusions

The first point I’d like to make with this piece is that the “winner” stat on its own does not give us an accurate portrayal of the aggression of a given player. Rafael Nadal might be the player who is most frequently misunderstood because of this phenomenon.

The second point I’d like to make is that the Monte Carlo final was indeed a fascinating match that featured plenty of elite clay tennis. 61% of the Key Points were won on Point-Ending shots rather than donated via unforced errors.

The third point refers to one of these individuals: it’s evident that one thing Nadal will look to improve upon is his return of serve. The match stats didn’t do him any favors: Djokovic was able to win 63% of points played on his 1st serve, and most crucially, 61% of points played on his second serve. And as we saw, the only way Nadal managed to win Key Points on Djokovic’s serve was due to unforced errors from the World Number One.

Nadal showed a more determined and aggressive mindset on his own serve in terms of Key Points won, but the challenge for him is to transfer some of that aggression to his return games. This starts, naturally, by stepping forward for his returns. Since the Spaniard’s remarkable comeback, he’s been stubborn in the sense that he’s stood far behind the baseline for returns. The thinking is that his agility is not where he needs it to be in order to step forward for returns, so he’s better served standing back and belting a monster forehand return (though in the latter stages of Indian Wells we did see Nadal occasionally moving forward for returns).

This has worked well so far (and will continue to work against lesser competition), but a baseliner of Djokovic’s pedigree won’t be too bothered by that kind of return stance. The reason is simple: Djokovic can take Nadal’s heavy ball on the rise (particularly off the backhand side). Thus, Nadal doesn’t get a chance to get back to the baseline, and it’s quite difficult to be aggressive during return games if one is running around near the back fence.

Again, Nadal isn’t having this problem in his service games: it’s purely a return game issue. I’m guessing that Toni will work with his nephew to make strides in this department, and we’ll surely see some improvement in Nadal’s upcoming tournaments. After all, the uncle-nephew combo has been historically excellent at correcting tactical issues, and the numbers (as well as the eye test) of the Monte Carlo are fairly indicative of what needs to be corrected.

Things I’ve Read Recently That Made Me Think

Fed Cup Posts Official Scorecards, Tennis Nerds Everywhere Rejoice (aka just me)– by Victoria Chiesa (Unseeded & Looming)

This is a most wonderful (and unexpected) development. I had my first encounter with scorecards during my week covering the Houston tournament. I noticed that the press could request any score card from the Media Director. He would then request it from the tournament referee. Naturally, to save himself some time, Pete Holtermann (the Media Director for the event) would request “popular” scorecards in advance, and distribute hard copies of them among the media members in the press room before a player would show up for a post match presser.

In the piece above, Victoria does an great job detailing how a scorecard should be read, as well as letting us in on how the whole process works (basically, the chair umpire is responsible for keeping track of all the information via that little gadget you see them tap into after every point).

Why are scorecards fascinating? Because they let you in on the story behind each game. No, you won’t get unforced errors or winners, but you will see the “story” of a set. For example, let’s say you see the scoreline of the Monte Carlo final. It reads “6-2, 7-6(1)”. You have no idea how the match developed. But with a scorecard, you’d be able to know that Nadal saved 7 set points. In fact, you’d be able to tell that Nadal saved 5 bagel points in the sixth game of the match. You’d be able to tell whether Nadal had to play those five points on first or second serves.

The scorecard would also give you key information about the second set, such as the fact that Nadal was up a break twice, and served for it at 6-5. It will also tell you that Djokovic broke Nadal in that 6-5 game by winning 4 straight points.

Apart from that, you’d be able to see that Djokovic clinched holds with aces twice in the match, and that Nadal handed Djokovic the first set via a double-fault. You’d also be able to find every single break point that took place during the match.

Is any of this vital information that everyone will be interested in seeing? Probably not. But there are those of us who would love to get a chance to look at a scorecard for any given match. And since this is an electronic system, I’m not sure why scorecards aren’t automatically posted after every single ATP, WTA, and ITF match.

The dynamic I saw in Houston indicated a very coherent system: the tournament (and the ATP) wanted the media to have as much information as they could in order to write about the matches that were happening. Why doesn’t this extend beyond the press room and into the internet? Hundreds of people write about tennis on a regular basis. Why not aid us in our writing by posting scorecards online when we’re not at the event?

Tweet That Got Favorited For Very Obvious Reasons

By losing third-set tiebreak to Carreno-Busta today, that's 14 straight tour-level TBs lost in a row for Robin Haase. Ties ATP record.

— Jeff Sackmann (@tennisabstract) April 22, 2013

Some context: this took place on Monday, during the opening round of the Barcelona ATP 500 (also known as the Open Sabadell, or in Spanish, the “Conde de Godó”). Robin Haase lost this particular match to the GOAT of the Futures circuit, Pablo Carreño Busta, in a third set breaker.

This is quite an “achievement” in futility for Haase, who was once a prominent prospect of the ATP tour. Injuries derailed his ascent, and he seems to be stuck in a bit of a funk (understatement alert): Monday’s match was Haase’s ninth first round exit of 2013. In fact, Haase finished 2012 on a strange run: after successfully defending his Kitzbuhel title (d. Kohlschreiber in the final), he lost 10 of his last 11 matches of the year. That included 7 first round losses, as well as 2 Davis Cup live rubbers.

Tiebreakers are intensely mental affairs, and confidence is as key an ingredient for success in them. What is noteworthy is that when I saw this tweet by Jeff Sackman, I immediately assumed Haase had been struggling, without knowing much of what he’d done in the past year.

The information in the second paragraph of this section, written after looking up Haase’s recent record for this column, came as no surprise.

Music Used to Write this Column

When people are asked about the band Genesis, most people think about Phil Collins and silly songs. I prefer to think of Genesis as the band where Peter Gabriel was the deranged frontman, and Collins was a superb drummer (as well as occasional vocalist). Wikipedia calls this incarnation “The Classic Era” of Genesis, and I think that’s an apt moniker.

I simply adore the first three albums produced by this band: Nursery Cryme (1971), Foxtrot (1972) and Selling England by the Pound (1973). I’ve been listening to them for over 15 years, and I’ve memorized most of the lyrics in them. However, I hadn’t paid them a visit in a while, and today seemed like a great day to do so. Much to my delight, Spotify has an album titled “Genesis: The First Songs Live.” It looks like a bootleg, and it sounds like a bootleg. Still, the dodgy sound quality doesn’t matter: gems like the entire “Supper’s Ready” suite (a 20+ minute extravaganza) and “The Musical Box” are there.

What’s also there is a strong reminder that this band was a beast live. That quintet was insanely talented, which is a good quality to have when you’re trying to play these intricate and gorgeous pieces of music.

Here’s the band, looking as young and nerdy as you’d expect in the early 70s (the guys were barely 20 or 21 years old at the time), performing for a Belgian TV station:

I realize now that I didn’t have YouTube as a teenager. There was no way for me to get to see videos of this band. It’s clear I would’ve spent endless hours back then watching all sorts of live videos like these.

I love living in the YouTube era.

If you have any questions or suggestions for topics to be covered in this column, feel free to tweet or email them to me. See you next week!

Interesting analysis of those stats Jose. One thing I noticed in so many write-ups about the match is everybody raving about the Djokovic return of serve, using superlatives that were (IMO) over the top – I mean, best returner in tennis history??? Yet your stats show he won hardly any Key Points on Rafa’s serve, correct?

I also liked one of the points you made in summary – “the “winner” stat on its own does not give us an accurate portrayal of the aggression of a given player. Rafael Nadal might be the player who is most frequently misunderstood because of this phenomenon.” I’ve long complained that the media doesn’t give Rafa his due. Invariable when Federer wins it’s because of his brilliance and Djoker is quickly getting similar treatment while Rafa wins because his opponents have bad days (which is, of course, ridiculous and not true). Rafa also doesn’t get credit for being such an intelligent tennis player. He’s not just a baseline grinder who wins just because of his athleticism, he wins because he’s so smart and he creates and sets up points, playing amazing defense when necessary to get himself into a position to hit a sizzling aggressive winner. All these stats you’re playing with might finally provide some facts to prove my contention. 🙂

Thanks, toot. About Djokovic’s return of serve, I think “best returner in history” is premature, but he’s certainly the best returner in the planet at the moment (Nadal has acknowledged as much more than once). And you’ll notice that Djokovic did win over twice as many key points on Nadal’s serve than Nadal managed on Djokovic’s serve(9 to 4).

In terms of the media giving Nadal his due, I think what happens is that most of the praise he gets doesn’t tackle a few key aspects of his game. He gets praised endlessly for the “fighting spirt” and “never say die” attitude, but very rarely for his tactical acumen and the consistency of his aggression (as measured by something like the Point-Ending Shots).

[…] The Backboard: Analyzing All the Key Points of the 2013 Djokovic-Nadal Monte Carlo Final – Juan José (changeovertennis.com) […]

But is nadal capable of these improvements?

Or Novak is too good and has no weakness.

I think if nadal has to win then he shd improve

His backhand and 2nd serve. Then he is somewhat

Level with Novak. What do u think Juan?